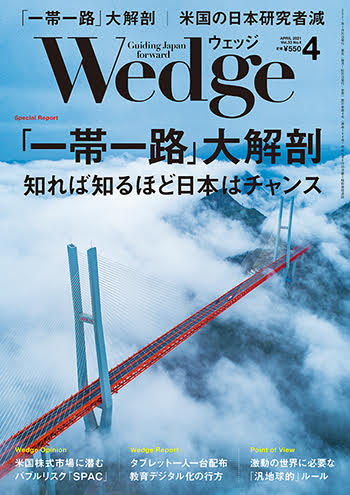

This article provides the full text of “BRI in Sri Lanka――More Than China’s Symbiotic Adventure” (by Jagannath P. Panda, Research Fellow and Coordinator of the East Asia Centre at MP-IDSA), of which the Japanese translated version was published in April 2021 Issue of Wedge (March 20, 2021).

Central Asia, Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia have often garnered prime importance in Chinese foreign policy outlook post the Cold War. In comparison, South Asia has been a somewhat overlooked sub-region in Beijing’s strategic ambit. There has recently been a subtle change in Beijing’s approach towards the sub-continent, with neighborhood politics pertaining to land and maritime issues gaining prominence in the country’s strategic calculus. One critical instrument of Chinese outreach toward South Asia has been Xi Jinping’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), earlier known as ‘One Belt, One Road’ (OBOR), under which Sri Lanka has emerged as a critical partner.

Although China and Sri Lanka share a “Strategic Cooperative Partnership” since 2013, their ties have been characterized by doubts and misgivings, particularly with respect to their infrastructure and connectivity cooperation. As an island and developing economy, Sri Lanka has openly welcomed Chinese financing and involvement in its connectivity projects and initiated a closer comprehensive partnership with the economic giant in the process. China’s expanding footprint in the region— and Sri Lanka in particular— has also translated into a budding military understanding between both states. Nevertheless, the maturing partnership is not without its woes; even as its China connect intensified, Sri Lanka has experienced a growing debate driven by concerns regarding China’s developmental aid and growing financial clout under the Maritime Silk Road (MSR) leading to a debt trap for the small economy state.

Sino-Sri Lankan Ties and the BRI

Historically, Sino-Sri Lanka ties grew bolder during Sri Lanka’s civil war with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), when Colombo faced increasing isolation on the international stage owing to rampant allegations of state-sponsored human rights abuses and civil right breaches. At a time when Sri Lanka was facing growing distance from the West and a bloody conflict within its own borders, China stepped forward to supply the state with financial assistance, military equipment and political cover at the United Nations so as to obstruct the expected decapitating international sanctions. China’s warm support, credited for the defeat of the LTTE in 2009, continued until 2015 as Beijing built a close rapport with the Rajapaksa family, and the small-power state began gaining critical importance in the South Asian outlook. In fact, President Xi Jinping was the first Chinese leader since 1986 to travel to Sri Lanka on a state visit in 2014, even authoring an article for a Sri Lankan newspaper highlighting the vitality of Sino-Sri Lankan friendship, connecting his “China dream” with President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s “Mahinda Chintana” philosophy, and calling for re-energized ties in pursuit of their shared vision. This synergy resulted in a robust engagement with massive Chinese loans and investments, including its involvement with the development of the Hambantota port. Nonetheless, whether Hambantota was a necessity in a country as small as Sri Lanka, especially as the primary port in the capital city was flourishing and had space for expansion, remained a point of wider debate within strategic communities in the country and elsewhere. Its approval highlighted the deep political clout China had developed in Sri Lanka, rather superseding its economic presence which usually paves the way for Beijing’s political prominence in foreign states.

Since their landmark “Rubber-Rice barter” agreement of 1952, which helped Colombo offset its deficiency of rice and find a market for its excess of rubber, and is often referred to as an “agreement of friendship”, Sri Lanka had become one of the first non-communist nation to form economic ties with China. In recent times, these economic exchanges – a point of reference in bilateral ties – have grown to encompass military, strategic and developmental contours. The BRI is heavily drawn on such a narrative. To China, Sri Lanka has hence emerged as a critical littoral state in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), and one that can act as a gateway to its engagement with the region’s maritime domain. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has historically adopted a party-to-party form of diplomacy, and shown a particular trend of working with small states that resemble autocracies like that of Sri Lanka.

With infrastructure being a vital need of the hour and considering India’s traditional role of influence in South Asia, Sri Lanka first approached New Delhi with it plans for its development needs. Colombo hoped that under India’s ‘Neighborhood First’ policy, both countries could deepen economic infrastructural cooperation and onset a new era of partnership. However, as former Indian foreign secretary and the national security advisor at the time, Shivshankar Menon, stated, the Hambantota port was “an economic dud then, and it’s an economic dud now”. India’s decision not to invest in the project paved the way for China’s entry, via BRI. Now, the inability of the Sri Lankan government to pay back loans undertaken under the BRI has resulted in China acquiring control of the port for 99 years – an infrastructure that lies at the strategic doorstep of China’s regional competitor, India, raising fears that Sri Lanka was set to be a ‘pearl’ in China’s ‘string of pearls’ in the Indian Ocean.

A Post-Pandemic Shift?

Sri Lanka’s participation in the BRI and the Hambantota episode has only resulted in China’s growing influence in the country. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s January 2020 meeting with Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa, who returned to power in November 2019, saw both sides pledging promotion of ties. They also affirmed their intentions to ‘jointly [forge a] China-Sri Lanka community with a shared future’, building on Xi’s ‘Community of Shared Future for Humankind’.

The port’s 99-year lease drew immense attention in the political and strategic circles with concerns growing regarding “debt trap” diplomacy that burdens small economies with unsustainable debt that could be paid in exchange for access to strategically placed infrastructure. Yet, Sri Lanka’s dependency on China meant that their engagement continued to grow, as seen especially amid the COVID-19 pandemic. In the past year, Beijing has granted Sri Lanka not only significant humanitarian and medical aid of over 50,000 masks and over 1000 COVID-19 test kits, but also provided it with USD 90 million grant, reportedly in an effort to reverse the existing “debt trap” narrative. These moves were in keeping with China’s larger ‘mask diplomacy’ strategy and its efforts to transition the BRI from an infrastructure-only initiative to a Health Silk Road that addresses new challenges created by the pandemic.

Beijing has also sought to highlight its Sri Lanka connect in the aftermath of – and quite possibly in reaction to – the high-profile Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad 2.0) second ministerial meeting between the foreign ministers of US, India, Japan and Australia on October 7, 2020. On October 9, 2020, a high-profile Chinese delegation held meetings with the Sri Lankan President and Prime Minister to expand Sri Lanka-China financial ties with the negotiations for a 10 billion yuan currency-swap agreement – much bigger than the USD 400 million Sri Lanka-India currency swap deal– to boost financial liquidity. Hence, despite widespread concerns of what a China-focused outlook might mean for the country, and despite the Sri Lankan Foreign Secretary admitting that the Hambantota lease was a “mistake” that must be corrected with an “India first” approach in terms of strategic security, China remains a vital partner for Colombo. Its developmental needs are such that the security discourse remains removed from the development narrative, making its China-connect a critical necessity. Rather, moving forward, Sri Lanka may attempt to adopt a hedging position vis-à-vis India and China in the region, and stick to a largely neutral stance that allows it to benefit from both nations simultaneously, and equally prioritize security with economic prosperity.

Although the Hambantota port is the most high-profile project under the BRI in Sri Lanka, it is by no means the only one. Other BRI investments in the country include the Colombo-Katunayake Expressway (or the Southern Expressway), the Mattala International Airport, the Moragahakanda Multipurpose Development Project, the Narocholai Coal Power Plaint, the Matara-Kataragama Railway Line, and the Colombo International Financial City (CIFC, or the Colombo Port City Project). The CIFC in particular entails investment worth over USD 15 billion; as a flagship project of the BRI, it has proven controversial since its very launch, with India being concerned about the maritime sovereignty and trade risks it poses. CIFC has been plagued by questions and accusations of lack of transparency, corruption and environmental implications, which resulted in its suspension pending investigation before it was restarted under a new agreement in 2016.

Such instances have added to the growing debate on the BRI’s underlying intentions and implications for small and medium power states participating in the project. Sri Lanka’s controversial case has in fact helped paint a nuanced picture of the BRI engagement with developing countries, highlighting its pros and cons, as well as its utterly intertwined nature with the participant countries. On one the hand, the BRI has enabled Sri Lanka to rebuild and grow its economy through improved tourism, trade and connectivity; on the other hand, it has raised critical questions pertaining to security and sovereignty. This dilemma has only grown more acute in the post-pandemic period, as Sri Lanka has only been forced to continue —if not enhance— its dependency on Beijing despite its own security-related concerns.

Navigating the BRI in a New Era

While “debt-trap” diplomacy of BRI is a legitimate concern –its effects seen most ardently in the Hambantota case –Sri Lanka is not in a complete Chinese debt-trap yet – its obligation to China adds up to around 6 percent of its GDP. Nonetheless, Sri Lanka’s high debt levels show that the country needs to improve its debt management frameworks. With BRI projects being delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic –the Colombo Port City project has especially faced multiple pandemic-induced problems –the time is ripe for Sri Lanka to strengthen its debt management abilities and implement such a strategy in future dealings with BRI.

Certain projects have contributed decidedly to Sri Lanka’s economy, such as the Colombo International Container Terminal (CICT), which has permitted the Colombo port to develop at a faster speed. However, increased imports from China for BRI projects in Sri Lanka have broadened the import/export trade deficit between the two nations, which has always run heavily in favor of China. At the same time, there have been restricted financial overflows and benefits for Sri Lanka beyond creation of infrastructure. Most work under the BRI projects is carried out not by local entities but Chinese-owned companies and workers. As a result, there has been negligible knowledge transfer to the local Sri Lankan work force for skill development under the Initiative. Future dealings under the BRI must account for these factors; Sri Lanka must negotiate more advantageous agreements that provide it with more comprehensive benefits.

For an island country like Sri Lanka, the environmental ramifications of Chinese projects in the country have also been a major source of concern. However, these are beginning to see correction in light of China’s own shifting focus to sustainable development, as evidenced by its recent release of the “International Development Cooperation in a New Era” strategy, which devotes a full section to the country’s objectives to contribute to the UN’s 2030 sustainable development agenda. While prior ventures were more destructive, later projects like the CICT, and Port City in Colombo have adjusted to stricter ecological principles under the guise of a ‘green’ Silk Road. To guarantee reliably high climate protection and environmental guidelines, Sri Lanka must reinforce its national rules while looking for additional ventures from green-investors.

Nonetheless, for Sri Lanka, and especially strategic stakeholder countries like India, fears that China will utilize foreclosed infrastructure and BRI projects for military reasons are driven by international tensions and Beijing’s continued revisionist tendencies. Keeping these in mind, Sri Lanka reinforced its maritime presence at the Hambantota port in 2018 by shifting its Southern Naval Area from Galle to the port. Yet, consistent oversight by policymakers, scholars and analysts is needed to ensure that there is increased transparency so that security-related concerns are adequately addressed and public trust in the initiative is restored.

Sri Lanka for its part must move away from foreign borrowing practices to focus on its trade and investments. In this context, as a small state without a large military, Sri Lanka must strategically pursue a more autonomous in the post-pandemic period. As US-China rivalry intensifies – and Sri Lanka’s largest trading partner, India, undergoes its own tensions and continued rivalry with China – it will be crucial for the small island power to protect its national interest vis-à-vis security over economy. This could occur via a well-founded and carefully thought-out dual track diplomacy that engages both the Indo-Pacific and China in a considerable manner, in line with the geopolitical realities of the current times. In other words, in the post-COVID-19 emerging international order, Sri Lanka’s foreign policy directives must focus on inclusion in frameworks such as the India-Japan-Australia envisioned Supply Chain Resilience initiative (SCRI), the creation of a maritime security partnership with India and Maldives, stronger political ties with the US and deeper trade ties with Indo-Pacific states – even as engagement with China’s BRI continues at a calculated speed.

■「一帯一路」大解剖 知れば知るほど日本はチャンス

PART 1 いずれ色褪せる一帯一路 中国共産党〝宣伝戦略〟の本質

PART 2 中国特有の「課題」を抱える 対外援助の実態

PART 3 不採算確実な中国ラオス鉄道 それでも敷設を進める事情

PART 4 「援〝習〟ルート」貫くも対中避けるミャンマーのしたたかさ

PART 5 経済か安全保障か 狭間で揺れるスリランカの活路

PART 6 「中欧班列」による繁栄の陰で中国進出への恐れが増すカザフ

COLUMN コロナ特需 とともに終わる? 中欧班列が夢から覚める日

PART 7 一帯一路の旗艦〝中パ経済回廊〟

PART 8 重み増すアフリカの対中債務

PART 9 変わるEUの中国観

PART10 中国への対抗心にとらわれず「日本型援助」の強みを見出せ

![]()

![]()

▲「WEDGE Infinity」の新着記事などをお届けしています。